Recently we designed a calendar for UNICEF and the University of Pauda; a project for 7D; and the final part of a design concept for Suavia, started a couple years ago and carried forward little by little, in harmony with the natural cycle of the vineyard and wine-making

Surmountable difficulties

Elsewhere I have addressed, and exalted, the figure of speech known as circumlocution, or the use of many words in place of one. Now I find myself exalting something resembling its opposite, namely the ellipsis, or leaving out words that aren’t essential to the comprehension of the phrase. This evolution of exaltation occurred after watching "Angel," a 1937 masterpiece by Ernest Lubitsch, who was born in Berlin and active in Hollywood since the early 20s.

The film is based on a classic love triangle, emotional and sexual, but not very original. A beautiful woman, insecure but in love with her husband (not very present, a little too sure of himself, but equally in love), is drawn into a relationship with another man out of boredom.

We know nothing of the woman, who is as beautiful as Marlene Dietrich; we know nothing of her in the present, nothing of her past. We find out that she got married after participating in a long meeting with the man that will become the lover. (The story is told through extended, yet brilliant and calibrated dialogues.) Halfway through the film, the two men come into contact accidentally discovering that they had met several years before. They quickly become friends and plan to get together over lunch with the woman of their desires - without knowing that she is lover to one of them and wife to the other. In the end, the triangle folds when the husband and wife decide that their feelings towards one another trump their securities of insecurities. The lover is left on his own.

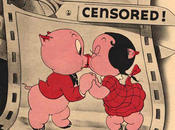

It is an elegant, rarified film full of dazzling scenes (with a couple of irresistible comic interludes with the service staff of the married couple) based on love, sex, and infidelity. However, the film is undermined by the dictates of the Hays Code, which required directors and producers at the time to censure sex to an almost ridiculous minimum. For this reason, the film is literally structured around gaps, reticence, innuendo, allusions, metaphors (the music becomes a memorable metaphor for sex). But only a genius with the 'touch' of Lubitsch could turn an castrating censorship not only into a strength of the film, but into the very core of a signature style that has made history and remains unmatched to this day.

From start to finish, the film doesn’t say anything, doesn’t show anything. It deliberately omits backgrounds, evolution or characters, key-situations, leaving almost everything untold. Instead the director provides us with an image, a picture, a phrase that is capable of evoking or connecting the untold scenes. Almost connecting them all. In this way, any viewer with normal attention span and insight should be able to construct, through reason, the details of the plot. Lubitsch leaves it to the imagination of the viewer to fill in the gaps. It’s one thing to understand something that someone explains to you word for word; it’s another to have to figure it out for yourself, based on your intelligence. (To explain something in an exhaustive, didactic way is to treat others as if there are stupid.) The elliptical dialogue provides someone with ordinary intelligence the opportunity to express themselves in creative terms, albeit with due caution, since you're still talking about a game of mirrors arranged by a great director and his writers (but, as mentioned, the viewer is still an active participant.)

This example demonstrates how the effectiveness of communication isn’t closely related to freedom of expression, or completeness of the information that is offered, and it's not a result of the much-vaunted brevity (the film takes a canonical hour and a half to illustrate an elementary and succinct plot). I consider the effectiveness emblematic, then as now, of inviting the viewer to participate directly in a game starring his own intelligence, capable of uniting various plots and sub-plots points without depending on traditional story-telling. The film evokes the happiness that I believe (and hope) everyone experiences when they feel their intelligence at work.

It is a lesson, even professional, that comes from a far away world, but that shines a light onto an increasingly connected and interactive future that I strive to understand. And it teaches us how thanks to seemingly insurmountable (i.e. strict censorship) can stimulate new creative ideas based on what’s not said and allowing us to appreciate the beauty of timeless masterpieces.

01/12/2014 Filippo Maglione